By David Murphy,

“Teach your children that we have taught our children that the earth is our mother. Whatever befalls the earth befalls the sons of earth. All things are connected.” — Chief Seattle, 1854

It’s that time in the political season when we’re at the beginning of a new administration. With President Donald Trump’s defeat of Vice President Kamala Harris at the polls, the hope of a new food and agricultural policy is now purportedly looking to take shape.

Branding itself as Make America Healthy Again (MAHA), the rise of a new movement evolved directly from RFK, Jr.’s concession speech in August, when he dropped out to endorse President Trump in the final months of the 2024 election. Since Trump’s victory, there’s been a lot of speculation about what RFK, Jr. can achieve as the head of Health and Human Services or HHS if he’s confirmed, and for some, it appears the ground is already starting to shift.

RFK, Jr.’s confirmation hearings will take center stage this week in Washington on Wednesday, January 29, and Thursday, January 30.

In his last week in office, the Biden administration finalized rules on a 2023 petition to ban red food dye #3, which some MAHA advocates count as an early victory. At the same time, the USDA made another long-awaited announcement regarding anticompetitive practices in livestock farming—a new poultry contract rule—but this decision didn’t receive as much attention.

Biden Admin’s Last-Minute Ruling on Poultry Contracts — Too Little, Too Late?

Like the ruling on red dye, farmers who fought for fair enforcement of the Packers and Stockyards Act for decades say the rule came up short by continuing to allow a corrupt tournament payment system that has pushed tens of thousands of farmers out of business in the past 30 years.

For many family farmers, this ruling on poultry contracts came too late, much like the Democrat’s failure to act on antitrust did for Iowa’s hog farmers and livestock farmers across America.

Since the summer of 2007, when Obama successfully campaigned across Iowa, promising to enforce antitrust laws and a Packer Ban, 37.3% of independent family hog farmers have gone out of business in Iowa alone.

In the past 18 years, Iowa has lost over 3,128 independent hog farms — an economic extinction event for rural communities that is rarely mentioned in the mainstream media.

The consequences of two Democratic administrations’ inaction on these critical issues have been devastating for rural America and the party’s vote totals in non-urban counties. But if anyone is waiting for Republicans to come to save the day, it may be a while.

According to Investigate Midwest, the new Republican chairman of the Senate Ag Committee, Arkansas Senator John Boozman, has received hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from Tyson Foods’ employees, and his Senate staff is full of former factory farm lobbyists.

RFK, Jr.’s Fight for Better Water Quality in Rural America

Full disclosure: I worked on RKF, Jr.’s presidential campaign in 2023 as his finance director or top fundraiser in 2023 from June until mid-October and left the campaign when I was asked to travel up to 30 to 50 percent of the time because I have chronic health issues. During my stint on the campaign, I traveled three times and got sick twice.

For what it’s worth, I first met RFK, Jr., in the summer of 2007 when I was asked to give him a tour of factory farm hog confinements in rural Iowa and again in 2017 when I set up an interview with him in then-Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard’s office in Washington, D.C., to interview him about glyphosate’s known harms before the lawsuits against Monsanto ever started.

In 2007, I worked with family farmers to protect Iowa’s declining water quality and the democratic ideal of local control, which allowed county elected officials the right to deny permits for factory farms in their communities if they saw fit.

In 1995, Iowans lost local control when House File 519 was passed by the Republican-led House and signed into law by Republican Governor Terry Branstad. This issue has become a political rallying cry for rural Iowans ever since, and the main reason I originally moved home was to try to help repeal the poorly designed law that turned the state into a safe haven for water-polluting factory farms.

As the lead attorney for the Waterkeeper Alliance, Bobby had worked with farmers in North Carolina and Iowa and was well aware of the problems farmers faced with a wholly rigged regulatory process that put them at a disadvantage in the marketplace.

Failure to properly enforce antitrust laws and the Packers and Stockyard Act made it harder for them to survive in cheap commodity markets, which gave major meatpackers excessive buying power and put family farmers out of business in record numbers.

Factory Farms and Industrial Ag’s Assault on Rural Independence

In the summer of 2007, I drove Bobby to a family farm in Independence, Iowa, just outside of Waterloo in eastern Iowa. I woke up at 4 am to drive over 2 and a half hours to meet Bobby and a group of 5 farmers in a local coffee shop in Cedar Falls.

Sitting in the small diner, the farmers were excited that morning because they had fought industrial ag and factory farms across their state when most farmers and elected officials had turned their back on small-scale farmers and the state’s rural residents.

It was a hopeful meeting, but one filled with the understanding that the then Democratic Governor Chet Culver and the Democratic-controlled House and Senate would not take a strong stance for clean water in Iowa and the state’s rapidly declining number of independent hog farmers. Politically, it may be hard to remember back to 2007 when Iowa Democrats controlled the Governor’s office and the Iowa House and Senate, something they had not done for 40 years.

The issue of factory farms and local control over factory hog confinements was so hot at the time that even Iowa’s Republicans pretended to care about it long enough to include it in their Party Platform for the 2008 election.

As the Iowa caucus slowly unfolded that summer, no one could imagine that in the first weeks of September 2007, political newcomer and first-term Illinois Senator Barack Obama would rise to the presidency.

The safe bet was on Hillary Clinton, while most of the farmers at the table believed that Senator John Edwards, whose farm and rural platform had come out strongly against factory farms and had called for a “Packer Ban” on giant meat conglomerates from owning the livestock that farmers raised and the corporations slaughtered.

The farmers’ main hope that morning was that the Packer Ban would limit price discrimination against small and midsized farmers and slow the expansion of corporate factory hog farms, which then controlled 20% of the market. In this process, the fair market price discovery process was increasingly being erased while packer profits were skyrocketing and farmers’ prices declined.

According to an article published in NPR, by 2014, Big Meat controlled 30% of “the hogs in the U.S. owned by packers like Tyson or Smithfield Foods.”

This now “captive market” has had a massive implication across rural America, as family farmers were rapidly being forced to take care of the livestock but increasingly seeing less and less of the profit.

As thousands of corporate hog factories were built across Iowa, the farmers only owned the debt on the massive factory farm buildings, which cost millions of dollars to build and maintain. At the same time, the growing meatpacking monopolies sucked up the profits.

For those who don’t understand economics, this is the short road to corporate serfdom for America’s farmers.

Today, the fully monopolized hog market controls over 60% of hogs owned by giant meatpackers. Thus, independent livestock producers no longer have a free market, and the price farmers are paid is no longer competitive but controlled by the meatpacking industry—the opposite of a capitalist “free market” system.

A lot of ink has been spilled in the mainstream media and D.C. talking points during elections, but the outcome is always the same. Politicians say one thing on the campaign trail, and reporters dutifully write it down. Everyone in the audience gets their hopes up while pretending people in Washington, D.C., will end up doing something. But if you’ve followed rural politics for the past 40 years, that’s mostly a lie.

Standing Up for Family Famers When No One Else Gives a Damn

In a recent interview with a reporter in D.C., I was asked if I had “ever witnessed Bobby display courage under fire,” and here’s my answer.

Besides RFK, Jr. being an environmental and public health attorney for the past 40 years, I told the reporter about one hot summer day when a worried mother of three showed us around her family farm.

Like the farmers at coffee that morning, Jayne and her husband were impressed that Bobby had been a part of lawsuits against Smithfield Foods even if it had been dismissed by a Florida judge in 2002 who did not understand how free markets are supposed to operate.

The Clampitts’ farm was just east of Independence, Iowa, a typical small Midwestern town with a population of just over 6,000 — 6,064 to be exact— that sits in the center of Buchanan County on the east side of the Wapsipinicon River, which eventually flows into the Mississippi River.

Real Threats and Intimidation Come to Rural America

That day, as Bobby and I went inside their house, we heard the engine of a large pickup rumbling just outside the window. Since speaking up in their community, the Clampitts had faced a campaign of covert intimidation and had even faced a death threat — a subtle, but intentional hint that if they weren’t quiet that hunting accidents happen “all the time.”

This was something that I’d already heard half a dozen times from various farmers and rural residents who had stood up to their neighbors to stop a factory farm from being built since I moved back less than a year earlier.

As we stood in her kitchen, Jayne described with increasing frustration how her neighbor, who was planning on building the 2,400-head factory hog confinement, had taken up the habit of parking in front of their house late at night, letting his truck idle, then slowly revving it for several minutes before driving off.

Their house was not far from the gravel road, just outside, and the message was clear. The neighbor had done this the night before and several nights in the previous months. He was sitting in front of their house with his truck running in the middle of the night and then driving off in a huff.

Word of RFK Jr.’s visit had most likely leaked in the small town of Independence before we arrived, where word of mouth traveled fast, especially when it was related to a major town dispute and their neighbor wanted to show he was not backing down.

I was no stranger to these tactics. I had moved home from living in Washington DC the year before because the farmer who was going to build the factory farm near my sister’s farm would get in her face to try to intimidate her, as would his handful of supporters. In our case, when my family refused to be quiet about it, someone had put a bullet hole in my parent’s office window in our hometown.

Bobby had also seen these intimidation tactics up close himself. When RFK, Jr. fought factory farms in North Carolina and other states across the Midwest, he was repeatedly followed by Nebraska rancher Trent Loos, who would sit in the front row of his speeches and try to scare him, wearing a large black cowboy hat and being a “shadow” at his major public events.

After standing in the kitchen for several minutes, their neighbor’s truck drove off, and eventually, we all went outside to look at their farm.

Jayne was sick not just at the prospect of being surrounded by factory farms but also by how lax Iowa’s state laws were as we walked down the gravel road in front of her house and towards a small wildlife area of roughly 350 acres that served as a public hunting area for residents and had what looked like a small pond.

As we returned from looking at the wildlife area and walking along the gravel road, the neighbor drove past us in his large pickup truck and crossed over the centerline, forcing us all to move slightly over to avoid the oncoming truck.

While Jayne told us more about her neighbor and his growing hostility, we witnessed it firsthand. Bobby and I stopped walking, stood on the left side of the gravel road, and just looked at each other.

Her neighbor didn’t bother to slow down like you usually would on a gravel road in the middle of nowhere, especially when your neighbors are on the road in front of their house. It was a completely unnecessary move designed to send us a message.

Dust from his pickup flew up briefly as gravel splattered against his truck’s undercarriage and tire wells. Bobby was calm and just shook his head. It was just another macho stunt by someone who knew they had the full force of the state’s industrial ag industry and all its politicians behind them.

In a calm but frustrated voice, Bobby explained that he had seen this bullying behavior before in his years of environmental activism and told us similar stories that had happened to small farmers in North Carolina he had worked with.

The Devastating Consequences of Bad Public Policy

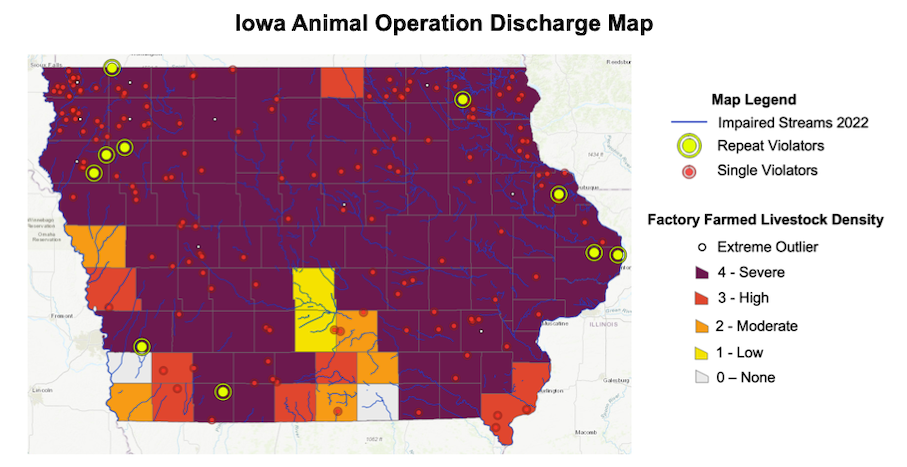

Iowa Factory Farm Density and Manure Spill Map 2022

If you can’t imagine the problem that rural Iowans face when dealing with a new factory hog farm moving next to their home, consider the fact that hogs shit at least 4 times more than a human, and when you put over 2,400 in one building that toxic brew of manure and urine adds up pretty quick on a daily basis. Especially when the massive cement pits larger than Olympic-size swimming pools are usually only emptied every 6 months.

Rolling Stone writer Jeff Tietz described the hellscape scenario pretty well in a December 14, 2006 article titled “Boss Hog.” The article captured the plight of rural residents fighting the rise of factory farms across rural America at the time.

“A lot of pig shit is one thing; a lot of highly toxic pig shit is another. The excrement of Smithfield hogs is hardly even pig shit: On a continuum of pollutants, it is probably closer to radioactive waste than to organic manure. The reason it is so toxic is Smithfield’s efficiency. The company produces 6 billion pounds of packaged pork each year. That’s a remarkable achievement, a prolificacy unimagined only two decades ago, and the only way to do it is to raise pigs in astonishing, unprecedented concentrations.” — “Boss Hog,” Rolling Stone

Iowa’s Third-World Water Quality

As a result, the excesses of Iowa agriculture have become famous for contributing to the Dead Zone. Factory farm manure and synthetic fertilizer applied to farmers’ GMO corn and soybean fields travel downstream and eventually end up in the Gulf of Mexico, where they choke out the oxygen from the water and lead to massive algae blooms the size of New Jersey.

According to Iowa environmental scientist Chris Jones, Iowa’s hogs alone produce more manure than 83.7 million people. If you add in the state’s dairy and beef cattle, laying chickens and turkey, the state’s factory farms produce the equivalent feces and urine equivalent (FEC) population of more than 168 million people each year.

This means that farmers across Iowa are spreading this unfathomable amount of waste across the entire state’s farmland while pretending that it’s just “fertilizer.” At the same time, Iowa’s politicians turn a blind eye to the pollution, and the Iowa Pork Producers and farm industry cover up all the harm this does to Iowa’s environment, waterways, and rural property values.

In the past 20 years, the number of livestock living on factory farms has increased by 78%, with the manure and waste load rising to more than 25 times that of Iowa’s human population.

This has had a devastating impact on the state’s water quality and drinking water for rural residents.

In 2024, at least 721 bodies of water in Iowa were considered degraded and “do not meet water quality standards for recreational use, public water supplies, and aquatic life protection.”

Today, at least “52% of Iowa’s assessed river and stream segments and 63% of the state’s lakes and reservoirs are impaired, meaning the water is too polluted for its intended uses,” such as drinking, recreation, fishing, and supporting basic aquatic life.

Scientists have found that the life-threatening bacteria E. coli, which is common in food safety outbreaks and found in livestock waste, is the leading cause of impairments overall, responsible for 62% of impaired waterway segments.

The rapid and unchecked expansion of factory farms across Iowa has created a water quality problem that rivals that of Third World countries.

Bad Public Policy Destroyed Iowa’s Landscape & Changed Rural Communities Forever

Factory farms have dominated Iowa’s rural landscape for the past 20 years. Gone are the small independent hog and livestock farms where livestock once dotted the landscape, living outdoors on pasture.

Iowa has a long history of being the leading hog-producing state in the country. Raising hogs used to be one of the most profitable ways for young farmers to make a living before factory farms started to be approved. Now, it’s difficult for young farmers to get started unless they’re willing to go millions of dollars in debt and take on that uncertain future.

In the past 30 years, since 1995, when the Iowa state legislature passed House File 519 that stripped local control from county officials, Iowa has lost a staggering 82% of its independent hog farmers.