European and U.S. bread differ in the type of wheat used, the chemicals added in the field and the fermentation process. These differences influence taste, nutrition and digestibility. Traditional European methods create cleaner, more nourishing loaves, while industrial practices in the U.S. prioritize convenience over gut health.

The Defender | Dr. Joseph Mercola | October 8, 2025

Story at a glance:

- Bread differs significantly between the U.S. and Europe due to wheat type, fermentation time and chemical use, which shape not only taste and texture but also how your body digests it.

- American bread often uses hard wheat with high gluten, shorter fermentation and chemical additives. This leads to denser loaves that strain digestion and trigger discomfort in sensitive individuals.

- Traditional European-style breads typically ferment for 12 to 48 hours, allowing microbes to break down gluten and sugars while enhancing mineral absorption, flavor and digestibility without chemical shortcuts.

- Glyphosate residues are more common in U.S. wheat, where the herbicide is sprayed before harvest, disrupting gut microbes and increasing health risks.

- Choosing or making bread with simple ingredients, like with real sourdough, lets you enjoy loaves that support digestion, provide nourishment and carry forward traditions of food craftsmanship.

You might have noticed it yourself or heard it from friends that the bread in Europe seems to sit differently in your body than the bread you eat in the U.S.

People share stories of enjoying baguettes in Paris or pizza in Rome without the discomfort that often follows a sandwich or dinner roll at home. Social media echoes the same theme, with travelers and health-conscious eaters asking why bread varies so much between regions.

The truth is that bread is not a single, uniform product. It reflects choices about farming, milling, fermenting and baking that vary from place to place. When you sit down to eat, your body is responding to those choices, and they add up to create a very different experience.

That divergence has roots both in the wheat itself and in how it is handled along the way, and it shapes not just the flavor and texture but how it interacts with your digestion and energy.

How wheat variety shapes the bread on your plate

When you think about what shapes bread, the type of wheat it’s made from is one of the most important details. In North America, much of the harvest comes from “hard” red wheat, which carries a high concentration of proteins.

In Europe, fields are dominated by “soft” wheat, which contains fewer proteins. Because those proteins are the raw material for gluten, the variety of wheat grown in each region sets the stage for different outcomes in bread texture and structure.

Gluten is a protein network, not a single substance

Gluten is formed mainly by two proteins called glutenin and gliadin. When flour is mixed with water, these proteins interact, stretch and form bonds that create elasticity in dough. Hard wheat contains more of these proteins, so the gluten matrix becomes stronger and more resistant to breaking.

This is why American flours are used for bagels, sandwich loaves and other breads that hold a dense structure and a chewy bite. Soft wheat, which dominates European fields, produces weaker gluten networks, resulting in breads that are airier and more delicate in texture.

Gluten load may influence digestive response

Bread made with high-gluten flour delivers more intact gluten proteins to the digestive tract. Gliadin, in particular, resists full enzymatic breakdown and reaches the small intestine in larger fragments, where it interacts with the gut lining and causes discomfort in sensitive individuals.

Climate and soil shape wheat cultivation

Hard wheat thrives in the hotter, drier regions of North America, while soft wheat is better adapted to Europe’s milder conditions. Over centuries, these growing environments shaped grain supplies and, in turn, local food traditions.

French, Italian and German breads often begin with soft wheat flour that naturally produces less gluten, aligning with regional preferences for lighter textures.

This difference does not mean that every loaf in Europe is low in gluten

Some European millers import hard wheat from North America and blend it into their flour to strengthen doughs for particular styles of bread.

While this practice exists, it’s difficult to determine how common it is, how much imported wheat is added, or how much it changes the overall gluten content in the final product. Still, the European grain system fundamentally rests on softer, lower-gluten varieties, while the American system tilts heavily toward harder, higher-gluten wheat.

What you experience when you eat bread is shaped long before the dough is mixed. The variety of wheat grown in one region versus another determines how much gluten is present and how it behaves under fermentation and baking.

That underlying difference helps explain why your body may feel a noticeable shift when you eat bread abroad compared with what you are used to at home.

Why slow fermentation makes bread easier to digest

One of the biggest differences between traditional and modern bread lies in how long the dough is fermented.

Extended fermentation gives microbes time to transform the dough, breaking down gluten and sugars while enriching flavor and nutrition. That process explains much of why slow-fermented bread often feels easier on the body.

- Microbes reshape dough during long fermentation — Many European bakeries maintain starters and ferment dough for 12 to 48 hours. These practices, handed down through generations, allow wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria to break down proteins and carbohydrates using enzymes such as proteases and fructanases. Proteases dismantle gluten into smaller, more digestible fragments, while fructanases reduce fermentable sugars that otherwise tax the gut.

- Fermentation improves flavor, texture, and nutrition — As lactic acid bacteria thrive, they produce organic acids that lower dough pH. This slows staling, adds flavor complexity and reduces phytic acid, which increases the bioavailability of minerals like magnesium and zinc. In effect, time allows microbes to act as natural pre-digesters, converting flour into a food that delivers more nutrients with less digestive strain.

- U.S. bread production often bypasses fermentation benefits — Commercial bakeries in the U.S. typically mix, proof and bake within a few hours, using commercial yeast and chemical conditioners to achieve volume and structure. The process is efficient but skips the microbial transformations of slow fermentation. Gluten and sugars remain largely intact, leaving bread with a different nutritional and digestive profile.

For a deeper look at how bread has changed over time and why your ancestors digested it differently than you might today, check out “The Truth About Bread — Why Your Ancestors Could Digest It (And Why You Might Not).”

Glyphosate use — A transatlantic divide in wheat production

Glyphosate has become a cornerstone of American wheat farming, used both to suppress weeds and, in some regions, sprayed directly on the crop just before harvest to speed up drying, make harvest more predictable and increase yield.

However, it leaves more opportunity for residues to remain on the grain that becomes your bread. This single step in crop management is an important place to look to understand why bread in Europe feels different.

In Europe, growers are bound by stricter rules

Farmers in Europe are not allowed to use glyphosate for pre-harvest desiccation, and its application throughout the season is more tightly regulated.

Countries such as Austria and Germany have gone further, pushing toward bans or national phaseouts. This reflects Europe’s broader precautionary approach to agricultural chemicals. For consumers, this means loaves baked in Europe are less likely to contain glyphosate traces.

Glyphosate disrupts gut microbes

Glyphosate works by blocking the shikimate pathway, an enzyme system in plants and bacteria. Human cells do not use this pathway, which is why regulators have often argued it is safe, but the bacteria in your gut do.

Disrupting those microbial communities affects digestion, immune regulation and even mood, since your microbiome interacts with nearly every part of your physiology. Animal and cell studies suggest glyphosate exposure alters gut flora balance and intestinal integrity, which amplifies symptoms in those with wheat sensitivity.

Global health authorities have raised broader concerns

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans,” citing evidence from animal studies and human data. Other concerns raised in the scientific literature include potential endocrine disruption, oxidative stress and links to metabolic disorders.

The way glyphosate is regulated illustrates how policy choices shape the food you eat. For a deeper look at how this chemical affects your body, read “Roundup Weedkiller Linked to Multiple Cancers.”

Additives, sweeteners and the engineering of modern bread

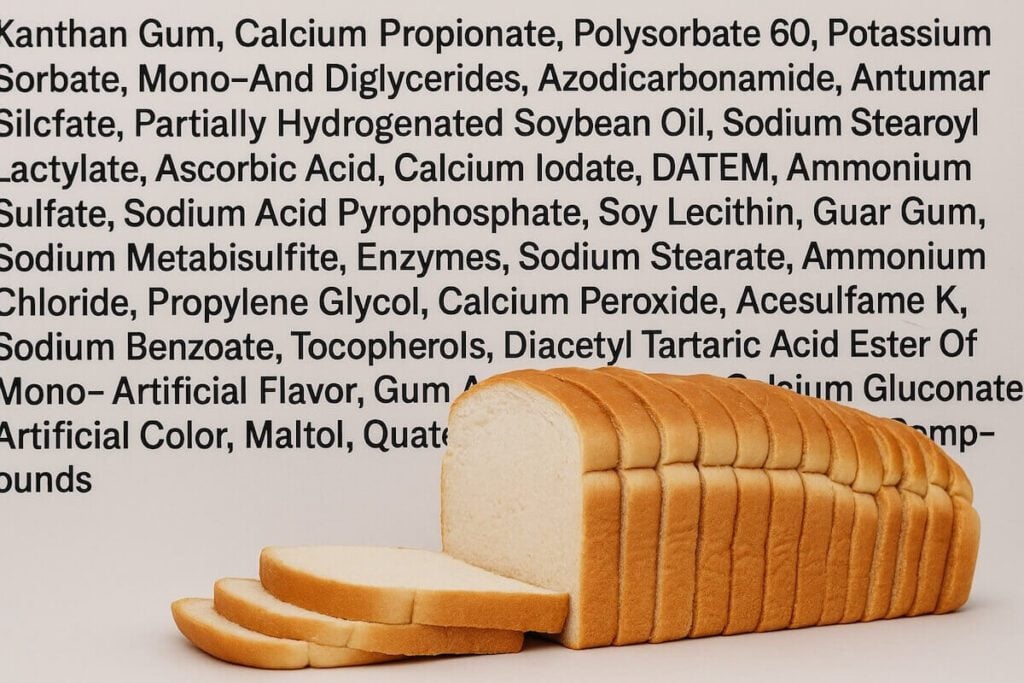

Bread is never just flour, water, salt and yeast when it comes from most large-scale commercial bakeries in the U.S. To achieve uniformity, speed and shelf life, they add a number of additives, preservatives and other chemicals that turn bread into as much of a manufactured product as a baked food.

Dough conditioners, oxidizers, and emulsifiers

Ingredients such as mono- and diglycerides, L-cysteine, azodicarbonamide and potassium bromate improve elasticity, gas retention and resilience under high-speed mixing. These compounds make mass production possible by shortening fermentation times and stabilizing loaves for distribution.

Potassium bromate, in particular, strengthens the structure and “spring” of dough, which is why it has been widely used by industrial bakeries. However, it’s not fully neutralized during baking, and studies show it increases the risk of cancer.

For this reason, the European Union, Canada, the U.K., China, Brazil and many other countries have banned it outright as a flour additive. Despite this, it remains legal in the U.S.

Bleaching and maturing agents

U.S. flour is often chemically bleached with agents like benzoyl peroxide and chlorine dioxide to create a whiter appearance and improve baking properties. Maturing agents accelerate protein cross-linking in the dough, again designed for speed and uniformity. The European Union bans or tightly restricts many of these compounds.

Mandatory enrichment and fortification

Since the 1940s, U.S. flour has been required to be enriched with iron and B vitamins to address nutrient deficiencies. More recently, folic acid was added to prevent neural tube defects.

While these measures sought to improve public health outcomes, they also underscore how much nutrition is lost when bran and germ are stripped during milling. European countries vary in their enrichment policies but generally apply less across-the-board fortification.

High-fructose sweeteners and other additives

Many U.S. breads include added sugars, often in the form of high-fructose corn syrup, to accelerate browning, enhance flavor and appeal to sweet-leaning palates. European breads, especially traditional loaves, tend to avoid this practice. The difference means that even when bread looks similar, the metabolic response in your body is not the same.

Taken together, these practices define two divergent approaches. One treats bread as a product engineered to endure long supply chains, and the other preserves bread as a food meant to be eaten fresh. For you, that difference shows up not only in flavor and texture but also in how comfortably your body receives it.

How to choose bread that’s good for you

If you want bread that reflects the qualities you notice in European loaves, the key is knowing what to look for. A few simple checks will help you identify breads that are closer to traditional formulas and easier on your digestion.

- Check ingredient lists for simplicity — The closer a loaf is to flour, water, salt, and starter or yeast, the better. Extra conditioners, flavorings or preservatives tell you that quality has been sacrificed for convenience.

- Choose authentic sourdough — A true sourdough loaf develops under the action of wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria over many hours. This natural process breaks down gluten fragments, reduces fermentable carbohydrates and produces organic acids that enhance flavor and extend freshness without chemical preservatives. When you choose sourdough, you’re choosing bread that is more digestible and closer to how bread has been made for centuries.

- Confirm the use of a real starter — Ask your baker about their starter and how long they ferment. Those who value tradition will be open about this, while shorter fermentation almost always indicates commercial shortcuts. On packaged bread, look for terms like “starter” or “levain.” If you see vinegar, lactic acid or yeast boosters instead, you’re looking at imitation sourdough designed for speed, not authenticity.

- Prioritize flour quality — Look for unbleached, stone-ground or high-extraction flours, as they retain more of the grain’s natural integrity and flavor. Many bakeries that follow European methods highlight their flour sources.

- Avoid loaves with added sweeteners — Commercial loaves in the U.S. often contain sugar, corn syrup or syrups that soften flavor and texture. Authentic European-style bread rarely relies on them because fermentation creates its own depth.

- Seek out local bakeries for transparency — Independent bakers often bake daily and are more transparent about ingredients and methods. By asking questions and choosing bread with long fermentation, clean ingredient lists and clearly sourced flour, you bring home loaves that reflect the standards you admire abroad.

- Reintroduce bread gradually into your diet if your gut is sensitive — If your gut health is compromised, the first step is not to load up on bread, even if it’s traditionally made. Complex carbohydrates feed microbial overgrowth and aggravate inflammation in a weakened digestive system. Begin instead with gentler sources of carbs, such as ripe fruits or well-cooked and then chilled white rice, which place less strain on digestion. As balance returns and symptoms improve, slowly add back more complex carbs, with slow-fermented sourdough being one of the best-tolerated starting points.

When you take the time to select bread made with patience and simplicity, you not only taste the difference but also feel it in how your body responds. Choosing bread made this way supports your digestion and connects you to a tradition of baking that values nourishment as much as convenience.

FAQs about bread

Q: Why does bread in Europe not bother me like bread in the U.S.?

A: You react differently because most European bread is made with soft wheat, longer fermentation and fewer additives. That combination produces less intact gluten, fewer fermentable sugars and more beneficial acids, which makes the bread easier on your digestion compared to the fast-produced, high-gluten, additive-heavy bread common in the U.S.

Q: Is sourdough bread really easier to digest?

A: Yes. Authentic sourdough goes through a long fermentation process where wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria break down gluten and fermentable sugars, which reduces digestive strain. If you’re sensitive to bread, sourdough is one of the best places to start reintroducing it.

Q: Does glyphosate in U.S. bread affect my health?

A: Yes, it can. In the U.S., glyphosate is often sprayed on wheat crops before harvest, which increases residue in the flour that ends up in your bread. Glyphosate disrupts gut bacteria, weakens the intestinal barrier and has been linked to other health concerns. European regulations are stricter, so bread there is less likely to contain glyphosate residues.

Q: If I have gut issues, can I still eat bread?

A: You’ll want to reintroduce it carefully. Start with gentler carbs like ripe fruit or well-cooked and chilled white rice until your digestion stabilizes. Then, slowly add back more complex carbs, with long-fermented sourdough as one of the best-tolerated options. This gradual approach helps your body adjust without aggravating symptoms.

Q: How do I know if sourdough bread is real?

A: Check the ingredient list. True sourdough only needs flour, water, salt and starter. If you see vinegar, lactic acid or yeast boosters, it’s likely imitation sourdough made to mimic flavor without the fermentation process — and it won’t give you the same digestive benefits.

Originally published by Dr. Joseph Mercola.