Wood Prairie Farm | Jim Gerritsen | March 20, 2025

Maine Tails

MAINE TALES Naked in New York. NYC, Circa 1993:

Feeding Elton John, Bread and Circus, and Dean & DeLuca in Manhattan or How Not to Get Skinned Alive as a Farmer in the Big City

We’d been warned. “Be careful,” the neighbors said. “When you sell into New York City, it’s a different world. Better make sure you get paid.” This was wisdom gleaned from the

experience of generations of Maine potato farmers. It was sound advice.

For farmers in Maine, New York has always represented an enormous market, way larger than Boston, but pockmarked with hazards that require everlasting caution. A deal in Maine is trust-based. A Boston deal is merchant-based. But business done in hyper-drive New York is a whole ‘nother kettle-of-fish.

A short twelve-hour-drive traverses the full American cultural spectrum from

neighborly down-home Maine to conquistador commercial culture personified by the lofty denizens of Wall Street and the New York Mercantile Exchange.

In the 1980s we started doing business with a small boutique produce distributor run by a young couple of brothers-in-law (one fellow was married to the other one’s sister). The

company was called ‘Bink & Bink,’ named in honor of the sister’s cat. For several years business went along well and trust grew.

That era was the peak baby-vegetable-craze of the 1980s. We started out shipping them

immaculate, hand-graded Fingerling heirloom potatoes which ended on hundred-dollar-dinner-plates in New York City’s top-shelf white-tablecloth restaurants.

Over time we also began sending Bink & Bink other baby potatoes and some of the

heirloom French Chantenay carrots we specialized in growing on our farm.

Early on, the owners at Bink & Bink shared their philosophy with us. It was something we

took to heart and fast became foundational to our way of doing business. They implored

don’t bother sending down anything except for the very best quality.

They added, take the time needed to do things right and then go ahead and charge

whatever price was needed to make the effort worth our while. They elaborated that their chefs might – and often did – complain about the price, but if you always supplied quality, the chefs would come back and continue to buy. Those standards were a good fit for our family-scale and maniacal-focus-on-quality-philosophy. We internalized that into habit and have remained forever committed to quality over quantity.

To get our goods down to NYC, we would buy space on the back of potato tractor-trailers headed down to produce market terminals in Hunt’s Point, Philly and Baltimore. Truckers

would drive all night leaving the truck brokerage south of us in Houlton around 6pm.

Like clockwork, twelve hours later at 6am, the Bink & Bink van would meet the truck at the Vince Lombardi Service Plaza on I-95 at mile marker 116.

In fifteen minutes they could finger off the load and both vehicles be back on their merry way.

We paid $200 for the trucker’s trouble and in those days that slightly sizeable amount made a nice little dent in the truck’s diesel bill. We always made sure that we had at least twenty pieces going down and so could add ten dollars onto each case to cover the cost of overnight shipping.

There was one morning during the middle of winter that Bink & Bink called us in a panic.

The very next night there was going to be some dazzling NYC gala in which Elton John would be providing the entertainment.

The chef charged with preparing the fancy dinner had his heart set on serving two-hundred-pounds of our Chantanay Carrots but Bink was plumb out. In exemplary New-York-style, to move an impossible ask into the realm of possibility, we were told money was no object.

Seizing upon the challenge and wanting to help our partners at Bink look good; we dropped everything and immediately re-configured our day.

Catching the truck broker and name-dropping Elton John – mind you, this was well-before the days of cell phones – he was able to secure passage on a potato truck which would be loading up with table stock that day and headed south that night.

We said we would pay $300 to get this load down to NYC. Then we ran the heaters in the carrot storage, unclogged the iced-up water lines and got our carrot wash line up and

running.

Pallet boxes of field-run Chantenay carrots were dumped into the hopper, washed with a re-fabricated potato washer, split-by-size and bagged up into twenty-five-pound Magic bags.

Just by the skin of our teeth we were able to load up, meet the truck in Houlton at six o’clock that evening and hand off a full load. The truck trip south went smooth and the transfer at Vince Lombardi came off without a hitch. That same night Elton John and the crème de la crème enjoyed their soiree which included some fresh heirloom carrots from Maine.

One spring, Bink & Bink asked us if we could secure fresh Fiddleheads for them to sell to

their fancy restaurant customers. We said we’d see what we could do. I checked around with a couple of local old-timers who had a casual seasonal gig of picking and selling these wild Maine delicacies which were in fact newly-emerged, immature and unfurled Ostrich ferns.

These local seasoned Fiddleheaders had their secret spots where they could pick hundreds and hundreds of pounds at their peak. With no dickering involved, we paid them their asking price and in turn bought piles of Fiddleheads for Bink to re-sell.

We set about rinsing off the Fiddleheads with cold water and packed them into plastic-bag-lined half-bushel cartons. Then we’d ferry a few hundred pounds at a time up to the airport in Presque Isle. In the shockingly informal and carefree days of pre-9/11, the cases would get loaded on as common air freight aboard an Eastern Airlines flight going down to one of the airports near NYC. With no door-to-door delivery involved, the rates were remarkably reasonable, rivaling UPS and arriving fresh in mere hours. The Bink & Bink van would meet the plane at the airport and New York restaurants could serve up fresh Maine Fiddleheads that same evening.

After several years of doing good business together, the train started de-railing for whatever reason any one of us might guess.

Checks from Bink & Bink started arriving later and later, until then they stopped coming altogether, with fibs and excuses taking their place. After many calls and broken promises, we explained that we would have to suspend shipping them any additional product until they cleaned up their balance due. It took most of a year but we finally did get paid.

By that time we’d already concluded that while we had enjoyed a good run, the goodwill had ebbed out. Bink had become a risk too great to bear, just as we’d been warned by our neighbors.

During the Bink & Bink years, one well-known and award-winning NYC chef had gotten

hooked on our Chantenay carrots. Out-of-the-blue this chef called us up one winter’s day and said he wanted to start getting carrots directly from us. So, we began shipping our carrots direct to his restaurant packing two sacks into a fifty-pound master carton with Net30 day terms.

The arrangement worked well the first winter and we would get paid on-time. Unfortunately, when we began shipping carrots again the next fall after harvest, it turned out to be a different story. We shipped and we shipped and we shipped, but didn’t get paid. Finally, we suspended shipments when the tally had swelled to two-thousand-dollars. In the end we were told the chef went under and we never did get paid. But, our neighbors had warned us.

We could see new changes brewing and dark clouds were on the horizon. Bigger farms,

especially out West, were getting into the organic deal and they had an economy of scale we would never match. Sales of potatoes in bulk-fifties were transitioning away from the specialty realm and becoming a faceless commodity. Prices were eroding.

Without a solid brand identity, we’d be sucked into the downward spiral and forced to accept a commodity price which might work for the big boys but didn’t work for us. We concluded we needed to build up our brand. That essentially meant switching over to packing into consumer sacks where our Maine family farm story could be successfully portrayed on the sack which end-users carted home.

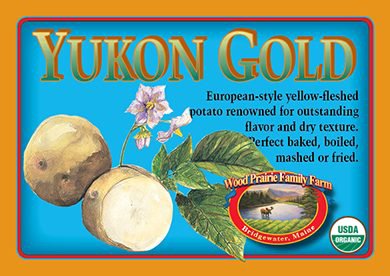

During the summer of 1992, Jenn Folk, a rather remarkable young college student worked for us. She was a talented artist and on rainy days she would paint pictures of our different potatoes: the tubers, the foliage and the beautiful colored blossoms.

We’d always been fans of Fruit Crate Label art from the 1920s and 1930s. We hoped we

could lean on that tradition and utilize Jenn’s paintings to create a series of distinctive sack labels.

Before Jenn went back to her family’s farm in Missouri, we collaborated with a graphic artist here in Maine and were able to invent our first themed set of “Potato Postcards.” We produced a series and each of our potato varieties had its own postcard.

Going to a Maine company we had them print off our Potato Postcards and they came out looking good, just as we’d hoped. In a bootstrapping, labor-intensive effort, we would take large rolls of two-inch-wide bag-closing crepe paper and chop it down into seven-inch lengths and folded the crepe pieces in-half, length-wise. Next we would hot-glue a Potato Postcard onto the crape.

Then, after filling and weighing a consumer sack of potatoes, we would stitch the bag shut with white thread through the colorful crepe using a Fischbein bag-sewer.

The presentation of the sewed bag with the artsy postcard was pretty eye-catching, and projected our brand.

We tracked down and approached a produce buyer at New England’s Bread & Circus natural food store chain and offered our spiel.

We promoted marketing tablestock potatoes by highlighting the strengths of each variety. This concept was one-hundred-eighty-degrees opposite to the entrenched industry-norm of selling anonymous generic potatoes as what the produce industry calls a “hardware” commodity.

We sent down a sample carton of our potatoes packed into potato-postcarded sacks. The buyer got right back to us and said B&C was interested. He ordered pallets of our potato sacks with the Potato Postcards to sell at their stores in and around Boston. They were an immediate hit.

Our bagged tablestock al a Potato Postcard business carried on with Bread and Circus for years. We sold them to B&C for $24.50 for a master case of (10) 3 lbs. sacks delivered to their distribution warehouse in Chelsea MA. In turn, B&C retailed them for $4.99.

One day soon after we got on B&C shelves, we got a call from a buyer at Balducci’s, the

gourmet market in Manhattan. He had seen our sacks of postcarded-potatoes at Bread and Circus and he wanted some. So, we began shipping cases of our bagged product down to his store.

Then, just a matter of days after those first sacks hit the shelves at Balducci’s, we got a

breathless call from an excitable fellow at Dean & DeLuca in Manhattan. He had just seen our sacks at Balducci’s, he wanted in, and there was a hint of desperation in his voice. Anyway, we set him up and we started shipping down cases of sacks down to Dean & DeLuca. Everything was looking rosy.

A week or two later, our fellow at Dean & DeLuca calls back and asked a question which left me baffled. “How d’ya tell what potato’s in the bag?” I believed I had heard him correctly but it made no sense. I struggled coming up with a reply, wanting to avoid insulting his intelligence.

So, with all the diplomacy a Maine farmer could muster up I replied, “Well, you see we

attach a Potato Postcard to the sack. That postcard tells you what variety’s inside the

sack.”

“No, no, you don’t understand. How d’ya tell what’s in the bag if there’s no card?”

Now we were getting somewhere. “There’s always a postcard. We always sew the sack shut with the folded-over crepe. The postcard is glued to the crepe. We always put the right postcard onto the right sack. That’s how you tell what’s inside.”

“Customers are stealing the cards off the bags. My shelves are full of naked bags. How do I tell what’s inside?”

Now as far as we know, our sacks have never been molested like this in back woods Maine or genteel Boston. Just guessing here, this must be the way art lovers in New York City convey their sentiment that some dirt farmers up in Maine did a pretty good job painting up them potato pictures.

Jim